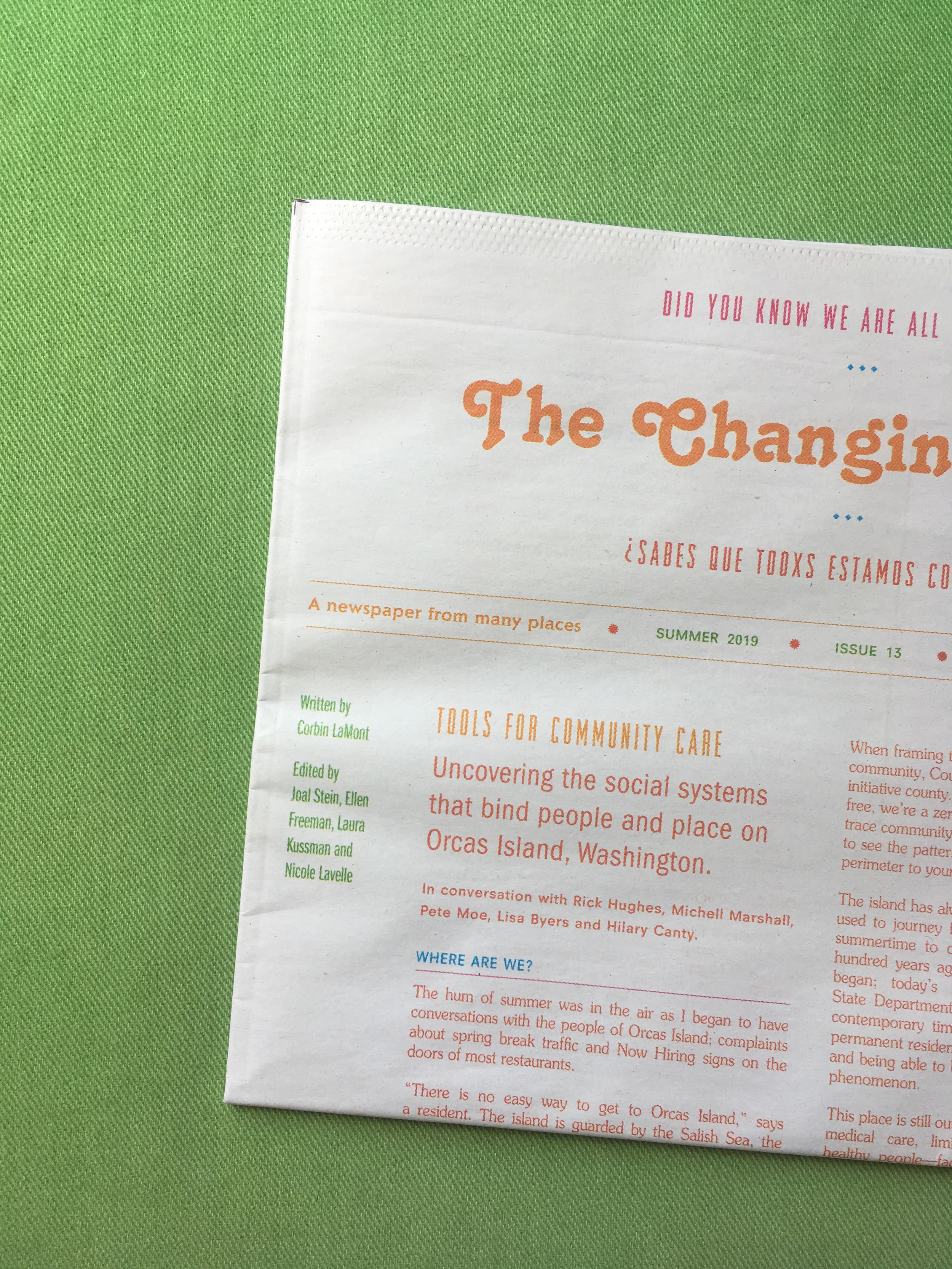

Issue 13: Orcas Island, Washington

Contributors: Rhys Balmer, Caroline Buchanan, Peter Fischer, Iris Graville, Colleen James, Jenny Johnston, Isaiah Kimple, Laura Kussman, Sara Leimbach, Jill McCabe Johnson, Hazel McKenzie, Cora Ray, Betty Reynolds, Anika Sanders, Colleen Smith, Evan Wagoner-Lynch and Annie Waugh.

Photos: Nicole Lavelle

Editors: Ellen Freeman, Laura Kussman, Corbin LaMont and Joal Stein.

Copyeditors: Amy Mae Garrett and Taylor Ross.

10.75" x 16.5" Cold Offset Press, Full Color.

Printed by Valley Printers.

Tools for Community Care

Uncovering the social systems that bind people and place on Orcas Island, Washington.

Written by Corbin LaMont in conversation with Rick Hughes, Michell Marshall, Pete Moe, Lisa Byers and Hilary Canty.

Edited by: Joal Stein, Ellen Freeman, Laura Kussman and Nicole Lavelle

In conversation with Rick Hughes, Michell Marshall, Pete Moe, Lisa Byers and Hilary Canty.

Where are we?

The hum of summer was in the air as I began to have conversations with the people of Orcas Island; complaints about spring break traffic and Now Hiring signs on the doors of most restaurants.

“There is no easy way to get to Orcas Island,” says a resident. The island is guarded by the Salish Sea, the permeable but ever present physical perimeter of this place. Yet Orcas Island, with nowhere near a tropical climate, was listed as one of “52 Places To Go in 2019” by The New York Times. Spanning 52 square miles, Orcas Island is the largest landmass of the San Juan Archipelago, a cluster of rocks, 172 of which have been named and are visible at low tide. Situated between the coastal city of Seattle, Washington and Victoria on Vancouver Island in Canada, Orcas Island is one of only four islands accessible by ferry in the archipelago. With around 5,000 people, Orcas has the second largest population of the islands next to neighboring San Juan Island where county offices are housed.

Over one third of housing (Caption 1) on Orcas Island are second homes occupied in the summer months that sit empty for the rest of the year. Conversations with longtime residents lead to concerns over disaster preparedness, or how visitors exceed speed limits while locals respect the posted pace. “We love the tourists” is a sentiment that usually rolls off the tongue with a bit of dry humor.

The primary industries of the county are hospitality and construction (Caption 2)—services for visitors and the building of those second homes. The fates of people are inextricably linked; if you live on an island you know this better than most. “Everything that’s here got here on a plane or a boat,” says Pete Moe, the executive director of the nonprofit recycling center and garbage transfer station on Orcas Island called The Exchange. When everything and everyone has to traverse the sea, there’s an extra level of awareness of the flow of infrastructure which can be invisible in places linked together by land.

When framing the mentality and governance of this island community, County Councilman Rick Hughes says, “It’s an initiative county. We’ve passed a local initiative to be GMO-free, we’re a zero waste aim community, we’re a leave no trace community, a nuclear weapons free zone.” It’s easier to see the patterns of big systems when there’s a physical perimeter to your place, guarded by the sea.

The island has always had accessibility limitations. Natives used to journey from the land by wooden canoe in the summertime to collect provisions for winter. Around a hundred years ago, private ferry access to Orcas Island began; today’s ferry service under the Washington State Department of Transportation began in 1951. In contemporary times there’s all this conversation around permanent residents, but the reality is that people wanting and being able to be on the island full-time is a fairly new phenomenon.

This place is still out of reach for folks who need consistent medical care, limiting access mostly to able-bodied, healthy peoplefifactors that cross economic lines. The predominant image of the island may be wealthy retirees with 60% of the population over age 50 (Caption 3) but there are also frequent stories of people who come here for live/work opportunities: YMCA camp Orkila, hospitality at Doe Bay Resort & Retreat, or construction jobs with camping options.

If the Salish Sea creates a physical barrier to this place, what other protections are in place? What safeguards a community? Concerns around affordable housing, social cohesion and the monopolization of resources are faced by communities around the world. What specific tools does Orcas Island have to combat these issues? What social systems keep people safe? How does Orcas Island care for the people of this rock in the sea?

Pride

Share and celebrate personal mythology.

There’s worry about keeping Orcas Island, well, “Orcas." There’s something about this word that is full of endearment. It’s a feeling; culture, community, attitude, safe haven, all rolled into the name of an island.

Everybody has their own origin story or personal mythology about what or who got them onto this rock in the sea. Usually this story begins with what I’ve begun to think of as “the ferry feeling." People remember their journey, whether to visit family, attend Camp Orkila, or be a kayak guide. There’s the moment where each person’s kinship to the island began.

Michell Marshall recalls when her husband first brought her out in 1998. “As soon as the ferry docked—I’m not kidding you—something inside of me went, ‘I’m home.’ I felt this immediate connection.” She was deep in her career at Microsoft in Seattle then, but he had bought land on the island for a time when they both might move away from the city. That ferry feeling would stick with her until she’d move out full-time over ten years later and begin running the local office supply and print store, The Office Cupboard.

Rick Hughes grew up coming out to the island, a part of a fourth generation family, but he still has those ferry feelings. “I can’t explain it but I get off the ferry and I feel like this weight lifted off of me.” There’s this permeable barrier, this transitional moment, where people have time—about an hour give or take—to take in the surroundings and be proud of their place in the world and proud of the place they live. The odyssey, the hero’s journey, these barriers allow for a deeper sense of home.

Beauty

Listen to the landscape.

Lisa Byers came here 25 years ago and began working with OPAL Land Trust a couple years later, a group that works to bring affordable housing to the island. Lisa says, “A common phrase you’ll hear people say when they choose to live in the San Juans is that they were first drawn by the beauty and they decided to stay because of the community.”

This sentiment is also echoed by the executive director of the Orcas Island Community Foundation and former EMT Hilary Canty. She says, “My feeling is the community is as beautiful as the environment, and that’s what keeps us here.” On Orcas Island, locals pick up litter and hold the bar high for respecting their place.

From where I was staying halfway up Buck Mountain, I could see Canadian islands in the distance. At night there were the ribbits of frogs and the hooting of owls. The water that surrounds you is clear and bright blue—yes, this place is undeniably beautiful. The sentiment echoed across age and wealth is the call of the natural beauty.

But with these stunning wildflowers and birdwatchers’ delights come downfalls as well. Lisa remarks, “The value of property is imbued by human desire.” The siren of this place has attracted the vacation home market as well. While still cheaper than the coastal urban centers, most of the housing stock is out of reach for those making their primary living from local industries.

Accountability

Create a support network face-to-face.

Of all the little quirks of island life, one in particular stands out. Michell puts it this way: “In the first three weeks of owning the shop, I remember thinking, ‘Something is different,’ and I couldn’t put my finger on it. Something was very different about this place. And then one day I go, ‘Ah!’ People actually talk to each other. They look at each other and talk to each other, and you see old talking to the young and visa versa, and that was something I wasn’t used to. Because at Microsoft you didn’t talk. If you said hello to someone it was like ‘What? Why are you speaking to me?’ So you’re used to being in that kind of world and this was very different. It was really friendly and open and that was really cool.”

I found this to be exceedingly true. Intergenerational conversations are par for the course, like the fact that the best friend of my host in her late twenties is a 60-some-year-old retiree. Or when musician Macklemore came to the island with his family it took all of about an hour for the gossip train to inform the public he would be attending a local dance performance.

Fodder for these conversations isn’t always current stuff. They can be fueled by an announcement in community newsletter Orcas Issues about someone falling ill, or a letter to the editor or the police beat in the island’s newspaper The Sounder.

People talk to each other, even people who don’t know each other. This is something that might be common in the southern states of the US, but is very uncommon for Pacific Northwest dwellers. Chitchat, gossip, and common conversation allow for accountability and attention to shared issues. These conversations also help get people connected to resources like work or housing.

Rick says about living here, “The best thing is the five-minute conversation with someone that you know that isn’t about anything.” Sometimes these conversations are not a few minutes though, Michell says. “I got to know everyone and I thought, ‘Well that’s kind of cool.’ Sometimes it was cool and sometimes it wasn’t cool. Like you went in the grocery store and you just wanted to pop in there for something, and then all of a sudden everyone is talking to you and an hour later you’re leaving. After a while that was hard.”

Being on time isn’t a familiar notion on Orcas Island, where people, meetings, and productions all seem to have whatever pace suits them best in the moment. An acceptable excuse for being late can be, “I ran into so-and-so.” These conversations might feel insignificant at the time, but they create an intricate web of relationships.

The island now has high-speed fiber internet available in some locations. Hilary vocalizes the effect of our ever-growing screen-time world: “In my neighborhood we’re not all democrats. We have different political views but we still have to sit and chat with each other. And how does that work? It works a lot better when we’re just sitting and chatting. It doesn’t work so well if someone reads a comment I made on someone else’s Facebook thread that they extrapolate into something I didn’t intend and suddenly you’re having bad feelings.”

People on Orcas Island see each other at the post office, the farmer’s market, the street, and through the 100+ service organizations. There’s plenty of opportunity to become accustomed with familiar faces and your neighbors. Yet at the governmental level, Rick explains, “...the most complaints are neighbor-to-neighbor complaints.”

Nepotism and entitlement are still alive and well on this idyllic island, but don’t try to think you’ll be able to get away with anything—the rumor mill has got their eyes on you.

Participation

Show up and join in.

“There’s this funny phenomenon that happens where you’d start a project at your house and you wouldn’t really tell anyone, but if it was a big enough project, everyone would show up,” Rick says. I heard alternate versions of this kind of thing happening where someone had a birthday party and decided it was the most pragmatic time to move a huge woodpile, a log hand-off line commenced, and drinking proceeded until the task was completed.

Hilary expresses a similar sentiment. “We do tend to take care of each other. At the end of my street is a family that homesteaded here. They still have the row boat that they used to row over to Anacortes when they were kids to get provisions, and they’re still here. It’s pretty amazing and I get to walk through their property everyday. And they don’t have a big gate, and I give them eggs, which I like. I assume that happens all across the island.”

There are the informal moments of exchange with one another that happen, but there are also more organized efforts, like how almost everything seems to be a fundraiser—whether that’s a catered senior brunch raising money for Meals on Wheels or electing the “Town Mayor” (which is actually a family pet put up for a campaign to raise money for the Children’s House).

These small-scale moments of working with the people around you allow for the mobilization of bigger efforts. Pete, the director of The Exchange, told me this story as I sat with him in their current building. “There was just a garbage dump here forever. Where we’re sitting now was the forest, with some little shacks and tents that the community had just set up organically to keep good stuff. It became a part of the local culture to use it. The county decided they didn’t want to run the garbage dump anymore—they wanted a big corporation to do it, or they wanted to put it out to bid. Us little guys over here in the trees knew if that happens there’s a really good chance they’re going to kick us out and not be interested at all in having any kind of reuse thing at all.”

When it looked like another company was more likely to get the bid, people showed up. Pete explains that “what we did have going for us was the public. There was a kind of email or a big plywood sign that went up somewhere: ‘The Exchange is going to get shut down, go to the public meeting.’ It was a county council meeting, and I wanna say like three or four hundred people showed up, which was unheard of on Orcas. So a huge crowd comes out, with a huge line for public comment. You can have three minutes to talk to the council. All of them were for The Exchange—that turned their heads: ‘Well maybe they can do it.’”

This small anecdote is one with a big, crucial lesson: people need to know they can make a difference, and that they have power. In a small-scale community the barriers to involvement are lower and it’s easier to make a difference with clear results. Connecting the dots, showing up, and noticing what needs to be done is critical to island life. Hilary explains access to services: “Our government is really over on San Juan County, so we’re a part of a county that is so dispersed. So for us, if someone has a mental health crisis, we’ve got to figure out how to get them from here to San Jaun. There’s this big group of helpers that help shepherd people from one place to another. Similarly, to access all sorts of services like SNAP or food stamps or veterans services, you have to have a navigator help you, and then usually the resource center brings a team over from vets to help, or we bring the dental van in for dental care, or we try to bring the services in when we can.”

Economic Inclusion

Recognize disparities and invest in services.

Income inequality in the United States is on an ever-increasing trajectory, a real-life game of Monopoly being played out in which the rich get richer and the poor get poorer. The Economic Policy Institute reports that income inequality has risen in every state since the 1970s, and in most states since the recession. We hear about this wealth gap as it pertains to Silicon Valley and San Francisco, but this is a trend not only in our coastal metropolises but from Wyoming to Texas to Missouri.

Washington State ranks 10th in the nation for income inequality (Caption 4). The data is based on the income of the top 1% in comparison to the bottom 99%. For Washington State the top 1% makes $1,383,223 on average per year while the bottom 99% makes $57,100 on average—those at the top make 24.2 times more. The disparity is only higher across Orcas Island’s home county of San Juan.

San Juan County ranks 37th in the nation with the top 1% making $2,004,457 and the bottom 99% making $50,582—that is, the top earners making 39.6 times more. These are big disparities that lead to questions around who has access to what, and whether we’re okay with some people having so much while others are barely getting by.

“We’re third in the nation for gifts per capita,“ Hilary says, “and that’s just the amount going out per person through the community foundation.”(Caption 5). Against the backdrop of a heated national conversation around wealth and income inequality and the drawback of public services, Orcas Island has maintained a strong ethos of supporting service organizations and charitable giving.

Rick sums this mentality up by saying, “No one really cares what you’ve ever done in the past, they really care about what you contribute to the community. This has always been a place where the billionaire, the waiter, the farmer, the shopkeeper, and the mechanic could sit at the bar or dinner and be equal and be friends. And that’s my biggest fear, an erosion of that kind of quality.”

Statistically there’s a pretty big middle class, but that is being put under pressure by a lack of access to affordable housing. Pride for economic inclusion must be backed up by support for people of diverse incomes on the island. That’s why organizations like OPAL Land Trust and services through Orcas Community Resource Center like the Dental Van are so critical.

Then you also have to factor in the differing realities of a full-time resident and a visitor. Hilary says, “To a lot of folks that are here part time, this is lala-land and that ‘community’ is where their real houses are, and where the issues are—and that there are no issues on Orcas. Over 50% of our kids are on free and reduced lunch at the school. So there are significant issues here.” At a house party this is described to me somewhat more intensely, with visitors seeing Orcas Island residents as characters on the dystopian sci-fi show Westworld.

Where is the push and pull of these differing realities and experiences of the island? Hilary says, “For some of them it’s going to be that they can’t find a gardener or a cleaner; finding a gardener or a cleaner in the middle of the summer is really hard. And the reality is, if you wanna be a cleaner you can make $35 to $40 an hour. If you want to work at the preschool it’s $14 max, so how do we make it possible for people to do what they’re passionate about?”

I went to the chiropractor while in town and he explained to me that of the eight graduates in his class, half stayed and half left to get an advanced education. He was the only one that came back to the island full-time after getting his degree. He was able to return and carve out a practice for himself on the island but that’s not the norm. People with degrees and people working trades are making the same amount of money; opportunity does not necessarily come with advanced education.

Orcas wants to be a middle ground, where people of divergent income do commingle and co-create their community. For now, there is an ethos that it doesn’t matter what you do or what you’ve done, it’s how you show up for your neighbor today and tomorrow.

Cultivation

Assess blind-spots and build bridges.

“The weirder it gets, the more normal it is. There’s nothing that surprises me here,” says Rick. Are you a free spirit or an artist? Do you live in your car? Do you have far-out political or spiritual views? This likely won’t raise any eyebrows on Orcas Island.

“There is a tolerance level that is huge. Most people here don’t really care what your neighbors do. Like, I have a thing with my neighbors; I don’t want a bullet on my land, and don’t cut my tree down, but other than that you can do whatever you want,” says Rick.

While island life on Orcas creates a tolerance for people that have made it onto the rock — the people that one sees on a daily basis—that doesn’t preclude there being a blind spot regarding who isn’t there. What is privilege if not being able to ignore those blind spots?

When Michell moved to the island and started running the Office Cupboard, she quickly became entrenched with local cultural affairs. She got involved with the Chamber of Commerce, and spearheaded both the Shakespeare Festival and a bird watching festival. As time went on though, she saw a need to bring different perspectives to the island. Orcas Island is staggeringly ~93% white with a ~1-2% Black population (Caption 6).

Michell says, “One of the things I noticed is that it’s so very white here, and I got a little tired of people saying things to me, the very same things that were said to me when I was younger. And I was like, ‘This can’t still be happening to me.’ It’s total full circle. Like, ‘I can’t believe these things are being said to me.’ So then I felt really pulled. Do I really want to be here? There were some pretty racist things, some pretty racist remarks.”

But art, she shares, “is enlightening to people.” She recounts going to a play in Seattle with her sister and her son, and while sitting in her seat she was in awe at seeing people of color, all colors. It was a shock when she realized she didn’t see people of color on the island unless she was looking in the mirror.

“And every time I wanted to see a production of professionals I had to go off island to see that. I thought, ‘No, I am going to create a non-profit and I am going to bring the people here, and I’m going to bring top talent, and I’m going to raise the money to do it.”

Since starting Woman in the Woods Productions she has been able to sell out shows of performance pieces centering people of color. She brought spoken-word artist Alex Dang into the schools, who has won acclaim for thought-provoking work like his piece “What Kind of Asian Are You?” She also recently hosted a sold-out fundraiser for upcoming productions and has struck up a partnership with Sozo Artists, Inc. out of Oakland to bring their talented roster of performers to the island.

Events are the workhorses of building community—getting people in a room together to share food, see art, have discussions and exchange ideas—and who is invited, seen, and represented at those events is often indicative of who feels welcome in a place.

It’s easy to be tolerant of people who look like you, think like you, and generally share similar values. It’s tougher to be tolerant of people who challenge your worldview. It’s even tougher to constantly be assessing your blind spots in that tolerance.

On Orcas, I saw many beautiful, humanity-reaffirming examples of tolerance, cooperation and general amicability. There were also many stories, anecdotes and private conversations expressed to me where someone was made to feel like they didn’t belong. While there are no bridges to the island, I saw the need for a different type of bridge to be built, one that actively works to build new bonds and connections.

This kind of bridge can be seen in Michell’s work to host cultural events from people with different racial backgrounds—to create a space for new stories to be told and new connections to be made.

Personal Expression

Support/encourage individual creativity.

A sandwich board in downtown Eastsound, the main (and only) commercial hub of the island, proclaims, “Open Mic Night at The Grange”. On the multiple community bulletin boards in town there are signs for a spoken word Open Mic at The Barnacle, another for Open Mic at The Lower Tavern, and another for Open Mic at Doe Bay Resort. If you want to get up on stage and share your talents, the monthly open mics stack up to about once a week. All of them offer a different atmosphere and somewhat different crowds, whether it be a stage at The Grange or the crowded candlelight of The Barnacle.

On Orcas Island, I found people to have a lot of enthusiasm for the talents of their neighbors. They were eager to tell me about the recent production they were a part of or of their friend’s band. Even with a small population, the island is currently home to three theater production groups. There’s a Playfest, a Film Fest, a Lit Fest, and a whole host of small and large scale productions happening at the Orcas Center.

Mamma Mia! recently had an 11-run show with a 100+ person production, selling out many of those shows. People perform and people show up, whether it’s to formal productions or a weekly jam session BBQ. For visual art, there’s the cooperative non-profit gallery Orcas Island Artworks and monthly shows at the Orcas Center. With so many outlets to create a culture of creativity, and if everyone around you believes they can make art, why can’t you?

Shared Values

Be thoughtful and take time.

On my visit to The Exchange, Pete and I say hello to the two men that are working on the construction of a new building and living on the property in their trailer during the build. One of the men has just made a roof rack out of recycling and it’s holding 5,000 lbs of wood. He yells out for us to admire his work. Commenting on the crazy nature of this newfangled roof rack, he adds, “Time runs differently on the island. On the mainland we are slaves to the time. Now we are here, we are relaxing.”

While tardiness may not really be a matter of concern on Orcas Island, people do seem to bring a certain amount of seriousness to life. This may be contradictory to the idea of carefree island life, but with great love comes responsibility. Pete says, “There’s this psychology that comes with an island: ‘Why would you throw something like an old wheelbarrow away when somebody else might want it?’”

Care and attention seem to be cultivated by island living. Lisa says, “There is something about islands that tends to have us bridge differences with people a little more thoughtfully, perhaps.” An island allows people to be more keenly aware; everything must come here by air or water and everything or everyone must leave the same way. An island demands a different level of attention and care. Those ideas of “somewhere else,” of “away,” of making people or garbage invisible, are trickier than when you’re landlocked. There are no suburbs.

Pete says, “In cities, garbage bills are usually a part of other utilities, so it’s a different relationship than taking your household trash to The Exchange and paying for its disposal directly.” A sense of disempowerment can be akin with modern life, whether this is in large urban areas with hard-to-navigate bureaucratic governance or in rural spaces where people are often disconnected from technological or cultural resources. An island creates a different relationship with one’s physical space in the world, demanding a present and focused mindset.

How are you willing to contribute to your place?

The Orcas Island Library held an event as part of the Coast Salish Speaker Series where Paul Che oke’ ten Wagner was invited to speak and perform. He is a member of the Wsaanich (Saanich) Tribe of southern Vancouver Island, British Columbia, and an award-winning Native American flutist. He spoke about how his grandmother would say, “We’re all flowers for each other,” and how his interpretation of this was, “You’ll never know when you might save someone’s life; even a smile can save someone’s life.”

So how do we show up for one another? Rick says, “Just be involved, open minded, engaged, and don’t take sides. Governance isn’t about winning or losing, it’s about compromise and moving forward. We have to sit people in rooms with opposing views and find a way to agree to move forward without getting angry, or personal or whatever. And that’s my mission: let’s not get so polarized. Be good neighbors, be good friends. Just communicate.”

This is not easy work, this is hard work. As Rick says, “There’s over a million people who come through here annually.” This takes involvement. This takes really showing up. Not everyone has the same ability to contribute, the creative versus the recluse versus the tourist or visitor.

Hilary thinks of her neighborhood. “What used to be cabins are now big houses, with people who aren’t here very often. There are 17 vacation rentals across the street from me. I don’t begrudge my neighbors for having rentals, but disaster preparedness? Those people are all going to need help.”

Can a visitor be a good neighbor? A good community member? Without as much accountability or shared values, part-time residents needs to bring a big dose of humility with them on their ferry ride.

I went out looking for the gatekeepers who keep this community what it is, but everyone is a part of this ecosystem. No one is looking out for our communities but us. Community is a verb and a shared responsibility. It can be harder to see in cities, but is as clear as day on an island.